📖 Mathematical economics#

⏱ | words

References

[Alchian and Allen, 1972]: Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, and 20 (pp. 2–52 and 384–404).

[Alchian and Allen, 1983]: Chapter 1 (pp. 1–12).

[Case, Fair, and Oster, 2017]: Chapters 1 and 2 (pp. 35–75).

[Frank, 2006]: Chapter 1 (pp. 3–26).

[Gans, King, Byford, and Mankiw, 2018]: Chapters 1, 2, and 3 (pp. 4–67).

[Gravelle and Rees, 2004]: Chapter 1 (pp. 1–10).

[Hamermesh, 2006]: Chapter 1 (pp. 3–14).

[Heyne, Boettke, and Prychitko, 2014]: Chapters 1 and 2 (pp. 1–44).

[Hirshleifer, Glazer, and Hirshleifer, 2005]: Chapter 1 (pp. 2–26).

[Kunimoto, 2010], p. 6.

[Malinvaud, 1972]: p. 1.

[Mankiw, 2003]: Chapter 1 (pp. 2-14).

[Perloff, 2014]: Chapter 1 (pp. 23–30).

[Vohra, 2005]: the Preface only.

[Waud, Maxwell, and Bonnici, 1989]: Chapters 8-10 (pp. 169-249).

What is economics?#

Economists try to explain social phenomena in terms of the behaviour of an individual who is confronted with scarcity and the interaction of that individual with other individuals who also face scarcity. This is perhaps best captured by Malinvaud’s definition of economics:

“· · · economics is the science which studies how scarce resources are employed for the satisfaction of the needs of men living in society: on the one hand, it is interested in the essential operations of production, distribution and consumption of goods, and on the other hand, in the institutions and activities whose object it is to facilitate these operations.” (Italics in original.)

– (From page one of [Malinvaud, 1972].)

Note

A definition of economics along these lines (that is, one that emphasises the importance of scarcity) can be traced back at least as far as Lord Lionel Robbins’ justifiably famous “essay on the nature and significance of economic science”. Chapter one of this essay contains a very nice discussion of the definition of economics and its history.

The first edition of this essay was published in 1932.

The third edition of this essay was published in 1984.

Core components of economics#

The presence of scarcity#

This is the defining feature of economics.

It is this feature that distinguishes economics from other social sciences.

In the absence of scarcity, economics would either not exist or look very different.

The behaviour of an individual who is faced with scarcity#

This involves the individual making a choice from a set of available (or feasible) alternatives.

The need to make a choice implies the existence of foregone alternatives and hence a cost.

The opportunity cost of something is the value of the best of the foregone alternatives.

Individual choice is often modelled using “constrained optimisation” techniques.

The interaction of individuals that face scarcity#

Economic equilibrium (eg competitive equilibrium and Nash equilibrium).

When does a system of equations have at least one solution?

How do we find such a solution (if it exists)?

How does any such solution vary with changes in the parameters (exogenous variables) of the economic system being studied? (This is known as comparative statics.)

Use techniques from linear algebra and (for nonlinear cases) fixed point theorems.

What is scarcity?#

Scarcity basically means that the availability of an item is limited relative to the desired uses of that item. Some important examples include:

Scarcity of income or wealth (a budget constraint);

Scarcity of time (a time constraint);

Scarcity of productive resources and technological limitations (a production possibilities constraint).

A budget constraint#

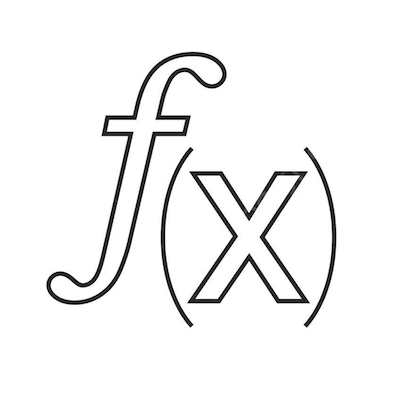

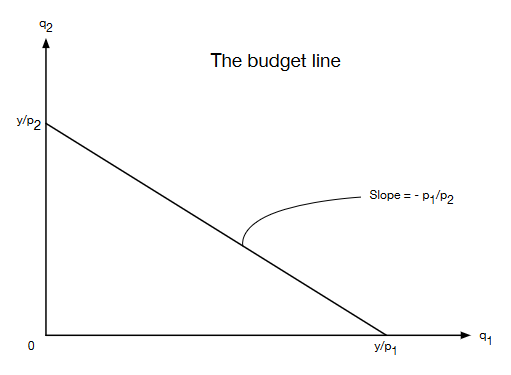

Suppose that there are two goods: Good one and good two. The price per unit of good one is \(p_1\) and the price per unit of good two is \(p_2\). The quantity of good one purchased by a consumer is \(q_1\) and the quantity of good two purchased by a consumer is \(q_2\). Note that the consumer’s total expenditure is \(p_1 q_1 + p_2 q_2\).

Suppose that the consumer’s income is \(y\). Ignoring the possibility of borrowing money from somewhere, the consumer cannot spend more than his or her income. This restriction is known as the budget constraint for the consumer. It can be represented mathematically by the inequality \(p_1 q_1 + p_2 q_2 \leqslant y\). We typically also impose non-negativity constraints of the form \(q_1 \geqslant 0\) and \(q_2 \geqslant 0\).

Fig. 1 The budget line#

Fig. 2 The budget set#

A time constraint#

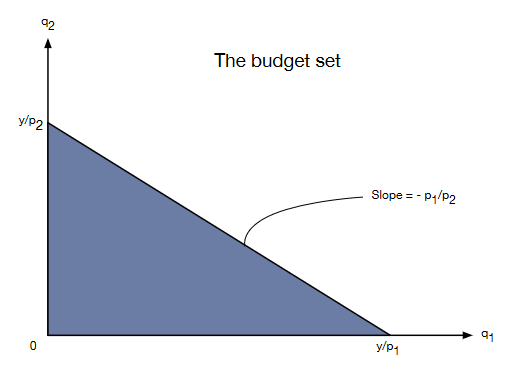

Suppose that there are activities that can be undertaken: Labour (N) and Leisure (L). The amount of time spent working is \(t_N\) and the amount of time spent relaxing is \(t_L\). Note that the total time that an individual spends on the various activities is \(t_N + t_L\).

Suppose that the total time available to the individual is \(T\). If we assume that every unit of time must be used for some activity, and that only one activity can be undertaken at any point in time, then the individual faces a time constraint of the form \(t_N + t_L = T\). We typically also impose non-negativity constraints of the form \(t_N \geqslant 0\) and \(t_L \geqslant 0\).

Fig. 3 A time constraint#

A production possibilities constraint#

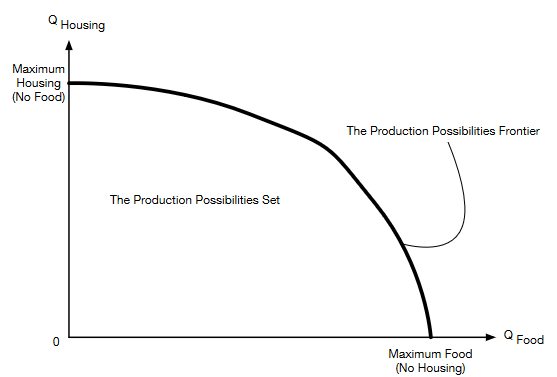

Suppose that there are only two goods that can be produced: Food and housing. Given the current state of technology and the current stock of productive resources, for any given feasible amount of one of the goods that is produced, there is a limit on the maximum amount of the other good that can also be produced.

If we graph the maximum amount of housing that can be produced for each feasible choice of an amount of food , then the resulting curve is known as the production possibilities frontier (PPF). This frontier can be represented by an equation of the form \(F(Q_F, Q_H) = 0\), or alternatively by an equation of the form \(Q_H = G(Q_F)\).

The PPF, along with the area under it (bounded by the axes because of non-negativity constraints on production), is known as the production possibilities set. This is the set of all possible feasible combinations of food and housing that could be produced under the current technology and resource constraints.

Fig. 4 A production possibilities constraint#

Scarcity and choice#

The presence of scarcity means that individuals and societies must make choices. When you are required to make a choice between various alternatives, you are implicitly giving up the opportunities that you do not select in order to obtain the opportunity that you do select.

In the context of a budget constraint, if an individual purchases one more unit of good X , then he must give up \((P_X / P_Y)\) units of good \(Y\). In the context of a time constraint, if an individual takes an additional hour of leisure, then he must reduce the time that he works by one hour. This means that he will earn less income. As such, he will have to reduce his consumption by some amount. In the context of a production possibilities constraint, if a society that is currently on its PPF decides to produce one more unit of good \(Y\), then it will need to produce fewer units of good \(X\).

Choice and cost#

When you select your most preferred option from the available alternatives, you are effectively giving up all of the other options that were available to you. The fact that you must give up alternative outcomes when you choose a particular option means that there is a cost associated with your choice.

Opportunity cost#

As we have seen, scarcity requires choices and choices impose costs. In effect, the existence of costs is intimately related to the presence of scarcity. Costs arise because you must give up some option (or options) in order to obtain something that you want.

Definition

The value to you of the best (most preferred by you) of the alternative options that you give up is known as the opportunity cost of the option that you select.

Note

In economics, the word “cost” should always be taken to mean “opportunity cost”. Note that this might not be the same as the accounting cost or the monetary cost of something.

The importance of constrained optimisation#

Given that scarcity is the defining feature of economics, it should not be surprising that constrained optimisation plays a central role in economic analysis. Indeed, constrained optimisation is very much a “bread and butter” skill for economists. It would difficult to make a living as an economist without some knowledge of constrained optimisation techniques.

According to [Ausubel and Deneckere, 1993] (p. 99):

“Almost every economic problem involves the study of an agent’s optimal choice as a function of certain parameters or state variables. For example, demand theory is concerned with an agent’s optimal consumption as a function of prices and income, while capital theory studies the optimal investment rule as a function of the existing capital stock.”

Economic interactions between individuals#

Most people are not hermits. In general, individuals interact with other individuals on at least some occasions. These interactions are an important component of the subject matter of economics. Economics is, after all, one of the “social” sciences.

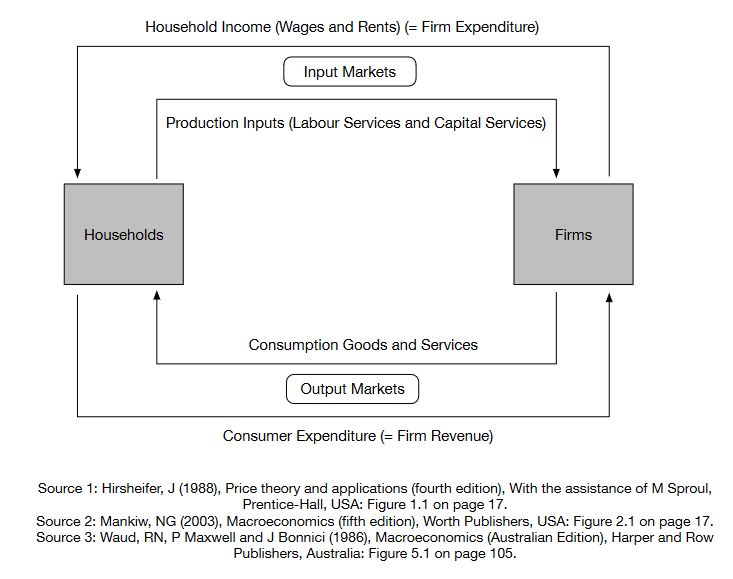

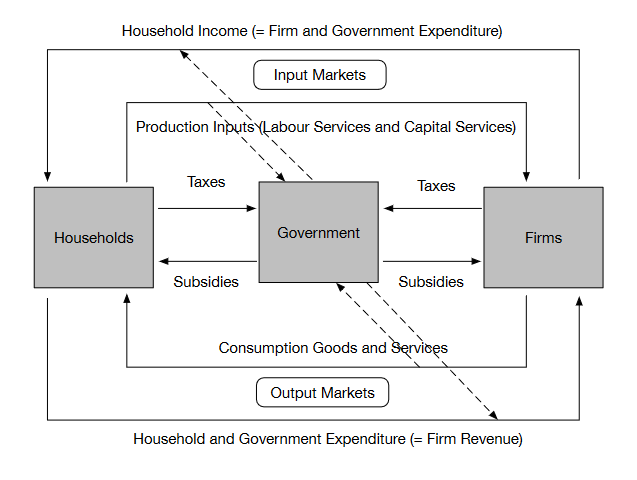

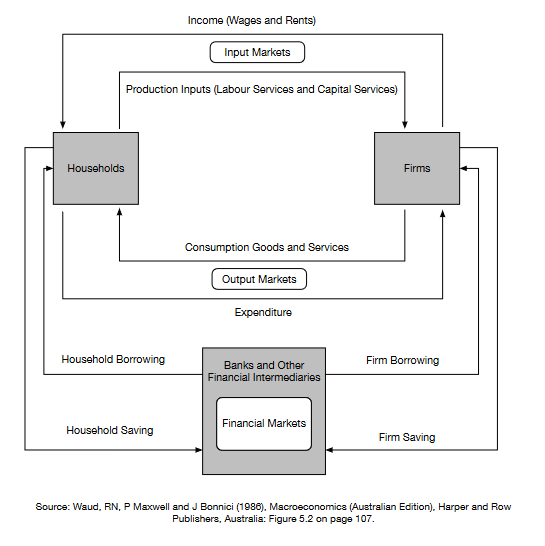

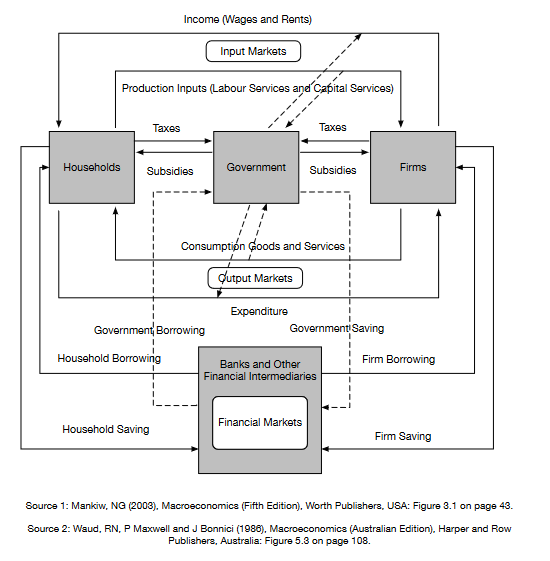

The interactions that occur between individuals that are important for economics take many forms and occur in many places. They include interactions in output markets, input markets and various institutions. Some of these interactions can be illustrated in a stylised diagrammatic representation of an economy known as a “circular flow of economic activity” diagram. These “circular flow” diagrams can incorporate varying levels of detail.

The next are some examples for a closed economy. While not being a formal economic model itself, a sufficiently detailed circular flow diagram can provide a very useful guide to the construction of a formal general equilibrium economic model of an economy.

Circular flow diagram examples#

Fig. 5 Circular flow example 1: households and firms#

Fig. 6 Circular flow example 2: adding government#

Fig. 7 Circular flow example 3: households, firms and financial markets#

Fig. 8 Circular flow example 4: households, firms, financial markets and government#

The three main components of mathematical economics#

Takashi Kunimoto (Unpublished lecture notes on mathematical economics, 18 May 2010, page 6) notes that, according to Rakesh Vohra (2005, Preface), the three core technical components that underlie much of economic theory are as follows.

Feasibility questions

Optimality questions

Equilibrium (fixed-point) questions

One of the main tasks of mathematical (micro-) economics is the provision of techniques to represent, analyse, and answer these three questions (and various other related questions).

Optimisation in economics: motivational quotes#

“For since the fabric of the universe is most perfect and the work of a most wise Creator, nothing at all takes place in the universe in which some rule of maximum or minimum does not appear.”

– Leonhard Euler in the introduction to De Curvis Elasticis, Additamentum 1 to Methodus inveniendi lineas curvas maximi minimive proprietate gaudentes, sive Solutio problematis isoperimetrici latissimo sensu accepti (1744).

“Constrained-maximization problems are mother’s milk to the well-trained economist.”

– From page 88 of Caves, Richard E (1980), “Industrial organisation, corporate strategy and structure”, The Journal of Economic Literature 18(1), March, pp. 64–92.

“Almost every economic problem involves the study of an agent’s optimal choice as a function of certain parameters or state variables. For example, demand theory is concerned with an agent’s optimal consumption as a function of prices and income, while capital theory studies the optimal investment rule as a function of the existing capital stock.”

– From page 99 of [Ausubel and Deneckere, 1993].

“The very name of my subject, economics, suggests economizing or maximising. · · · So at the very foundations of our subject maximization is involved.”

– From page 249 of Samuelson, (1972), “Maximum principles in analytical economics”, The American Economic Review 62(3), June, pp. 249–262. This journal article is the text of Paul Samuelson’s Nobel Memorial Prize Lecture from 11 November 1970.