📖 Vector and matrix arithmetics#

⏱ | words

References and additional materials

[Sydsæter, Hammond, Strøm, and Carvajal, 2016]

Chapter 15 whole

Excellent visualizations of concepts partially covered in this lecture, strongly recommended for further study 3Blue1Brown: Essence of linear algebra

Matrix#

Definition

A matrix is an array of numbers or variables which are organised into rows and columns

An \((n \times m)\) matrix takes the following form:

\(n\) and \(m\) are dimensions of the matrix A

An \((n \times m)\) matrix has \(n\) rows and \(m\) columns

Note that, while it is possible that \(n=m\), it is also possible that \(n \neq m\)

Definition

Matrix with has the same number of column as rows, \(n=m\), is called a square matrix.

Scalars and vectors#

Definition

A scalar is a real number \((a \in \mathbb{R})\)

Definition

A column vector is an \((n \times 1)\) matrix of the form

A row vector is a \((1 \times m)\) matrix of the form

Vectors can be thought of as matrixes with one dimension equal to \(1\)

Scalars can be thought of as \(1 \times 1\) matrixes

Matrix arithmetic#

Scalar multiplication of a matrix

Matrix addition

Matrix subtraction

Matrix multiplication: The inner, or dot, product

The transpose of a matrix and matrix symmetry

The additive inverse of a matrix and the null matrix

The multiplicative inverse of a matrix and the identity matrix

Note

Many binary operations with matrices are not commutative! (order of operands is important)

Let \(A\) is an \((n \times m)\) matrix takes the following form:

We will assume that \(a_{i j} \in \mathbb{R}\) for all

Scalar multiplication#

Suppose that \(c \in \mathbb{R}\). The scalar pre-product and post-product of this constant with this matrix is given by

Note that \(c A=A c\). As such, we can just talk about the scalar product of a constant with a matrix, without specifying the order in which the multiplication takes place.

Examples

Matrix addition#

The sum of two matrices is only defined if the two matrices have exactly the same dimensions.

Definition

Two matrixes are called conformable for a given operation if their dimensions are such that the operation is well defined.

Suppose that \(B\) is an \((n \times m)\) matrix that takes the following form:

The matrix sum \((A+B)\) is an \((n \times m)\) matrix that takes the following form:

Note matrix summation is also commutative, \(A+B=B+A\).

Exercise: Convince yourself in this fact.

Examples

Matrix subtraction#

Matrix subtraction involves a combination of (i) scalar multiplication of a matrix, and (ii) matrix addition.

As with matrix addition, the difference of two matrices is only defined if the two matrices have exactly the same dimensions.

Suppose that \(A\) and \(B\) are both \((n \times m)\) matrices. The difference between \(A\) and \(B\) is defined to be

In general, \(A-B \neq B-A\)

Example

Under what circumstances will \(A-B=B-A\) ?

Solution

We can work with matrices as variables in the equation!

Matrix multiplication#

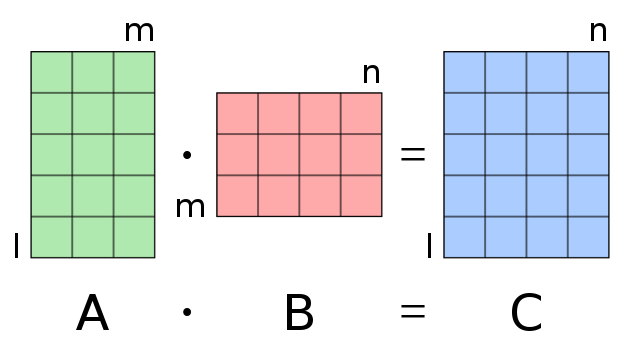

The standard matrix product is the dot, or inner, product of two matrices.

The dot product of two matrices is only defined for cases in which the number of columns of the first listed matrix is identical to the number of rows of the second listed matrix.

If the dot product is defined, the solution matrix will have the same number of rows as the first listed matrix and the same number of columns as the second listed matrix.

Let \(B\) be an \((m \times p)\) matrix that takes the following form:

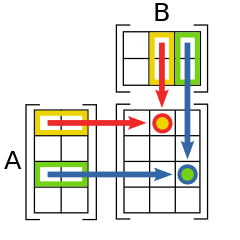

The matrix product \(A B\) is defined and will be an \((n \times p)\) matrix. The solution matrix is given by

Fig. 37 Matrix multiplication: conformable matrices#

Definition

A dot product of two vectors \(x = (x_1,\dots,x_N) \in \mathbb{R}^N\) and \(y = (y_1,\dots,y_N) \in \mathbb{R}^N\) is given by

Fig. 38 Matrix multiplication: combination of dot products of vectors#

Fact

Matrix multiplication is not commutative in general

Example

Note that \(A C \neq C A\).

Note

Do not confuse various names for the two types of matrix/vector multiplication:

Dot/scalar/inner product denoted with a dot \(\cdot\) is the sum of products of the vector coordinates, outputs a scalar

Vector/cross product denoted with a cross \(\times\) is a vector that is orthogonal to the two input vectors with a length equal to the area of the parallelogram spanned by the two input vectors (not covered in this course)

Matrix transposition#

Suppose that \(A\) is an \((n \times m)\) matrix. The transpose of the matrix \(A\), which is denoted by \(A^{T}\), is the \((m \times n)\) matrix that is formed by taking the rows of \(A\) and turning them into columns, without changing their order. In other words, the \(i\) th column of \(A^{T}\) is the ith row of \(A\). This also means that the jth row of \(A^{T}\) is the \(j\) th column of \(A\).

The transpose of the matrix \(A\) is the \((m \times n)\) matrix that takes the following form:

Examples

If \( x=\left(\begin{array}{l} 1 \\ 3 \\ 5 \end{array}\right) \) then \(X^{T}=(1,3,5)\).

If \( Y=\left(\begin{array}{ll} 2 & 3 \\ 5 & 9 \\ 7 & 6 \end{array}\right) \) then \( Y^{T}=\left(\begin{array}{lll} 2 & 5 & 7 \\ 3 & 9 & 6 \end{array}\right) \).

If \( Z=\left(\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 3 & 7 \\ 4 & 5 & 11 \\ 6 & 8 & 10 \end{array}\right) \) then \( Z^{T}=\left(\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 4 & 6 \\ 3 & 5 & 8 \\ 7 & 11 & 10 \end{array}\right) \).

In general, \(A^{T} \neq A\).

Definition

If matrix \(A\) is such that \(A^{T}=A\), we say that \(A\) is a symmetric matrix.

Example

\( A=\left(\begin{array}{ll} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{array}\right)=A^{T} \)

\( B=\left(\begin{array}{ll} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{array}\right)=B^{T} \)

\( C=\left(\begin{array}{ll} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array}\right)=C^{T} \)

\( D=\left(\begin{array}{ll} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{array}\right)=D^{T} \)

Fact

If \(A\) and \(B\) are conformable for matrix multiplication, then

Null matrices#

Definition

A null matrix (or vector) is a matrix that consists solely of zeroes.

Example

For example, the \((3 \times 3)\) null matrix is

Fact

For an \((n \times m)\) null matrix and an \((n \times m)\) matrix \(A\), it holds \(A+0=0+A=A\).

Definition

Suppose that \(A\) is an \((n \times m)\) matrix and \(\mathbb{0}\) is the \((n \times m)\) null matrix. The \((n \times m)\) matrix \(B\) is called the additive inverse of \(A\) if and only if \(A+B=B+A=0\).

The additive inverse of \(A\) is

Fact

Identity matrices#

Definition

An identity matrix is a square matrix that has ones on the main (north-west to south-east) diagonal and zeros everywhere else.

Example

For example, the \((2 \times 2)\) identity matrix is

Fact

For an \((n \times n)\) identity matrix \(I\) it holds:

If \(A\) is an \((n \times n)\) matrix, then \(A I=I A=A\).

If \(A\) is an \((m \times n)\) matrix, then \(A I=A\).

If \(A\) is an \((n \times m)\) matrix, then \(I A=A\).

Definition

Let \(A\) be an \((n \times n)\) matrix and \(I\) be the \((n \times n)\) identity matrix. The \((n \times n)\) matrix \(B\) is the multiplicative inverse (usually just referred to as the inverse) of \(A\) if and only if \(A B=B A=I\).

Only square matrices have any chance of having a multiplicative inverse

Some, but not all, square matrices will have a multiplicative inverse

Definition

A square matrix that has an inverse is said to be non-singular.

A square matrix that does not have an inverse is said to be singular.

We will talk about methods for determining whether or not a matrix is non-singular later in this course

Fact

The transpose of the inverse is equal to the inverse of the transpose

If \(A\) is a non-singular square matrix whose multiplicative inverse is \(A^{-1}\), then we have

Example

Note that

Note that

Since \(A B=B A=I\), we can conclude that \(A^{-1}=B\).

[Haeussler Jr and Paul, 1987] (p. 278, Example 1)

Idempotent matrices#

Definition

A matrix \(A\) is said to be idempotent if and only if \(A A=A\).

Clearly a NECESSARY condition for matrix to be idempotent is that \(A\) be a square matrix (Why?)

However, this is NOT a SUFFICIENT condition for a matrix to be idempotent. In general, \(A A \neq A\), even for square matrices.

Two examples of idempotent matrices that you have already encountered are square null matrices and identity matrices.

We will shortly encounter two more examples. These are the Hat matrix \((P)\) and the residual-making matrix \((M=I-P)\) from statistics and econometrics.

Example

The \((2 \times 2)\) identity matrix:

The \((2 \times 2)\) null matrix:

Econometric application: classic linear regression model#

One of simplest models that you will encounter in statistics and econometrics is the classical linear regression model (CLRM). This model takes the form

where \(Y\) is an \((n \times 1)\) vector of \(n\) observations on a single dependent variable, \(X\) is an \((n \times k)\) matrix of \(n\) observations on \(k\) independent variables, \(\beta\) is a \((k \times 1)\) vector of unknown parameters and \(\epsilon\) is an \((n \times 1)\) vector of random disturbances.

In the CLRM, the joint distribution of the random disturbances, conditional on \(X\), is given by

where 0 is an \((n \times 1)\) null vector, \(l\) is an \((n \times n)\) identity matrix and \(\sigma^{2}\) is an unknown parameter.

Matrices associated with the CLRM#

The ordinary least squares estimator (and, in the case of the CLRM, maximum likelihood estimator) of the parameter vector \(\beta\) in the CLRM is given by

The hat matrix for the CLRM is given by

The residual-making matrix for the CLRM is given by

The hat matrix is symmetric#

The hat matrix is idempotent#

The residual-making matrix is symmetric#

The residual-making matrix is idempotent#

Determinant of a matrix#

Determinant is a fundamental characteristic of any matrix \(A\) and a linear operator given by a matrix \(A\)

Note

Determinants are only defined for square matrices, so in this section we only consider square matrices.

we use some sort of recursive definition

Definition

For a square \(2 \times 2\) matrix the determinant is given by

Notation for the determinant is either \(\det(A)\) or sometimes \(|A|\)

Example

We build the definition of the determinants of larger matrices from \(2 \times 2\) case. Think of the next definitions as a ‘induction step’

Definition

Consider an \(n \times n\) matrix \(A\). Denote \(A_{ij}\) a \((n-1) \times (n-1)\) submatrix of \(A\), obtained by deleting the \(i\)-th row and \(j\)-th column of \(A\). Then

the \((i,j)\)-th minor of \(A\) denoted \(M_{ij}\) is

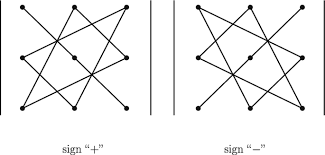

the \((i,j)\)-th cofactor of \(A\) denoted \(C_{ij}\)

cofactors are signed minors

signs alternate in checkerboard pattern

for even \(i+j\) minors and cofactors are equal

Definition

The determinant of an \(n \times n\) matrix \(A\) with elements \(\{a_{ij}\}\) is given by

for any choice of \(i\) or \(j\).

given that the cofactors are lower dimension determinants, we can use the same formula to compute determinants of matrices of all sizes

Example

Expanding along the first column:

Expanding along the top row:

We got exactly same result!

Fact

Determinant of \(3 \times 3\) matrix can be computed by the triangles rule:

Examples for quick computation

Properties of determinants#

Important facts concerning the determinants

Fact

If \(I\) is the \(N \times N\) identity, \(A\) and \(B\) are \(N \times N\) matrices and \(\alpha \in \mathbb{R}\), then

\(\det(I) = 1\)

\(\det(A) = \det(A^T)\)

\(\det(AB) = \det(A) \det(B)\)

\(\det(\alpha A) = \alpha^N \det(A)\)

\(\det(A) = 0\) if and only if columns of \(A\) are linearly dependent

\(A\) is nonsingular if and only if \(\det(A) \ne 0\)

\(\det(A^{-1}) = \frac{1}{\det(A)}\)

Example

Compute the determinant of the \((n \times n)\) matrix

Fact

If some row or column of \(A\) is added to another one after being multiplied by a scalar \(\alpha \ne 0\), then the determinant of the resulting matrix is the same as the determinant of \(A\).

very useful in practical computation of determinant exercises!

In other words, the determinant is invariant under elementary row or column operations of type 3 (see next lecture).

we will talk about this next week

Where determinants are used#

Fundamental properties of the linear operators given by the corresponding matrix

Inversion of matrices

Solving systems of linear equations (Cramer’s rule)

Finding Eigenvalues and eigenvectors (soon)

Determining positive definiteness of matrices

etc, etc.